After work, in the afternoon, to the shop to buy various bits, and then pack a bag. The rucksack, which had been 13.9kg with equipment less about two kilos of batteries, Kindle, notebook and pens and trail poles, was 22kg on the eve of departure – all up: all clothing, all food, and some water. Heavier than I anticipated, but manageable. Where had that weight crept in from? This was to be my ninth solo backpacking and wild camping adventure. To Cromford then, and by train to London.

Arriving in London I had a bit of time – trains in the UK are just not reliable enough to cut things fine and not leave plenty of time. I was at St Pancras at 19:38 for a 21:15 train out of Euston, up to Scotland. Why was I travelling from the Midlands down to London to go back up to Scotland? Because the alternative was taking the train to Crewe and picking up the sleeper there at midnight. If you’re going to wait for a couple of hours on a draughty railway station platform at night, I don’t recommend Crewe. I did that once; it won’t be happening again. I had a pint and a sausage roll in the Betjeman Arms at St Pancras, then strolled along the Euston Road to join the sleeper to Inverness, the longest train in Britain, and my carriage right at the front of the train.

I slept well enough on the train and had to hurry through my full Scottish breakfast in a paper bag. I found myself on the platform at Newtonmore at 07:15 on a drear and misty morning, barely starting to get light. I dragged on everything I had, to keep warm, and in Goretex over-trousers, gaiters, waterproof jacket, gloves and woolly hat, set off into the pre-dawn gloom. I had in reserve only a thin Rab mid-layer and at that point in the morning wondered if I had come onto the hill ill-clad. I walked out of town up onto the heath; had there been no mist this would have been glorious and scenic. You could tell it was a temperature inversion – there’s a look about the sky when you can sense that radiant blue sky and sunshine are only inches, as it were, above the steel-grey ceiling of mist.

I ascended the Calder River up Glen Banchor, meeting no-one, listening to the fearful noise of stags rutting. This noise reminds me, with my taste in films, of the zombie apocalypse. At one point I needed to take care fording a stream. Late morning, I was approaching a tin hut somewhere round 648984, where the map marks “township” at Dail na Seilg. A stalker strode out to speak with me. We had a polite conversation about my plans, and his plans, and I saw that I needed to change my plans. It suited me to do so, to be fair – it wasn’t simply a matter of me rolling over. That said, this is pure stalker’s country, not at all walker’s country. I followed a tired old land-rover trail and became aware I was going in the wrong direction. I was soon lost and disoriented in the brown upland, stumbling over the heather looking at my compass. It took some close map and compass work to get me onto the right trail, a good and substantial unmade road, which I followed south-west down Strath-an-Eilich.

Early afternoon I came out at Castle Cluny, a nice-looking Scottish Baronial pile in the usual grey granite. Through the delightful autumn colours I trod through the grounds out onto the road. Without a detour, there followed a tiresome 2.5km tramp along the A86, a single track road at this point, but still with a fair amount of traffic. This brought me to Laggan, around about 3pm. From here, another tarmac road tramp of 4.5km brought me to the “Spey Dam”. I had not been aware I was walking up the Spey valley. I met no mountaineers or walkers. At this point, around 4pm, I’d been 7-8km on metalled roads and much of the rest of the distance on good unmade roads. I admit that had I known so much of this route lay along actual roads, I might have chosen differently.

Resting by the dam, I saw a couple of cyclists whizz past. I set off along the road under the dam and arrived at a kind of industrial yard, with piles of rubble and hardcore, and big spotlights ready to be connected to a generator – there’s no mains electricity here, even though this countryside isn’t the ostensible wilderness of the Cairngorms. All around there are very robust and well-maintained deer fences, with proper access for vehicles and pedestrians at the appropriate places. At this point, early though it was, I was looking for a place to camp. I could continue along the unadopted and private metalled road along the north side of the reservoir created by the dam, or I could hike uphill into more wild country further up Glen Markie. I opted for the former. I went through a metal gate, pulling back the bolt. The bolt made a displeasing sound that in the pristine silence of that place, sounded like a lamb being slaughtered. I walked a hundred yards before repenting of my decision and turning back. Such sudden changes of mind have served me well in the past. Being willing and able to change your mind is a virtue, not a vice – don’t let anyone tell you that stubbornness is a virtue.

I detoured uphill into Glen Markie for about an hour, past a wasteland of industrial plantations, until I came across a place where I might camp. I would have to hike back downhill to the reservoir tomorrow morning, but this was more or less where I thought I would end up when planning this trip as a desktop exercise back in June. I camped near the ford of the Allt Tarsuinn Mor, just before it joined the Markie Burn, a substantial river. I had a very cramped and limited pitch, but it had the advantage of being bone-dry heather. I was just below the tributary stream as it flowed down a ravine into the main river. I could hear running water in three different registers: the roaring or rushing of the river, the chuckling of the brook over stones, and the sound of small waterfalls. In spite of the limited pitch, it was supremely comfortable and I took one of the best nights’ sleep for some years, from around 7.30p.m right around until well after 6.30a.m next morning. I had a completely dry strike and was away from camp around 9 o’clock. There was no hurry. In any case, at this time of year in this place, daylight comes late and lingers late. There was little usable daylight much before 7.30a.m.

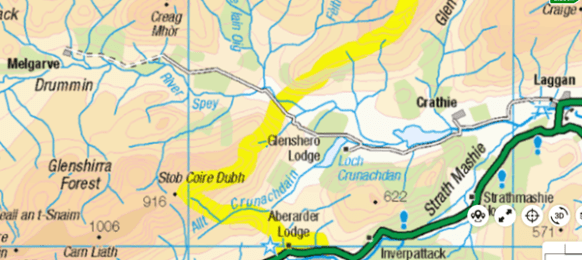

I hiked back down to the bottom of the glen, and turned right, resuming my route of the afternoon before. There followed 12km along metalled road – a single track road through glorious, empty country – but a metalled road all the same. The adopted part of the road (that is, the part coloured in yellow on an OS map) ended at Garva Bridge. Here there was an ancient bridge of 18th century military origin. Two cyclists whizzed past. I stopped for lunch and sat between the road, the woods and the Spey, under the cathedral of a clear blue sky. Today’s weather was better than yesterday’s. The tarmac gave out at a place called Melgarve – an empty house. At this point, in the heart of the Monadliath, you’re about 16km from the main road at Laggan, and perhaps a little further from Fort Augustus.

Beyond Melgarve, first a very conspicuous “Road Closed” sign, secondly, an actual half barrier blocking the way ahead to vehicles. The road itself continues up into Corrie Yairack, though without benefit of tarmac. This is one of “General Wade’s Military Roads”; to walk this route is why I was here. The afternoon’s walking ahead of me was the crux and heart of my trip.

To the chagrin of some, a mighty high-tension power line marches up the valley, into the corrie and up and over the pass. All should have access to electricity. I remember in the 1980’s hitch-hiking in the Lake District and getting a lift from an estate agent. He told me that the Friends of the Lake District – every one of them living in a home with electricity – had opposed the building of power lines over a wild valley, which would have brought electricity to houses that did not at that time have access to power. Ever since then I’ve had little patience with the sort of environmentalist who sits in comfort opposing construction that would being the same comforts to others.

Near the foot of the pass proper, I met a cyclist, the first outdoorsperson I had spoken to in days. I had seen no walkers, nor even so much as a footprint, along this route. The crux of the pass was six zig-zags, six legs of which were at this time of day (mid-afternoon) walking directly into bright sunshine. I was bareheaded. I had not thought to bring a sun hat, though I did have sunglasses. I blazed up the zig-zags barely out of breath. I’ve had eye trouble this year, and for that reason I chose this route because it was not so physically challenging. I also reflected that I have become successively more physically fit, particularly upper body muscle tone, on each one of these nine solo camping expeditions I have undertaken since 2021. I came off the hill on that first trip and had some unpleasant muscle problems in my shoulder, and had to visit a sports physiotherapist at the cost of several hundred pounds. Since then, on the advice of the physio, I try to do regular upper body strength exercises. Coming down to the Dungeon Ghyll last October, after two hard days on the hill, I was absolutely shattered – and part of me, misses that feeling. Being immensely tired sharpens one’s appetite for the simpler comforts in life –a hot shower, clean clothes, a Nice Hot Cup of Tea, a pint of beer and a pie, a warm bed.

At the top, a squalid guard-house stood, with an open door and bunks visible inside. In the long and golden afternoon I followed the path down towards Fort Augustus. I passed a 4WD vehicle with three fellows in it clearly observing deer. Another thing I noticed which I found unusual, was overflight by a small fixed-wing aircraft – repeated overflight, three or four times. Helicopters would be unremarkable, but a light aircraft, I found unusual: this is wild country. It was certainly not a sight-seeing flight. Far more interesting and dramatic mountains are available within a few minutes flight time for even a light aircraft. My best guess, looking at the heading and direction it was taking, was that some form of commercial survey was taking place, probably of the power lines in the valley.

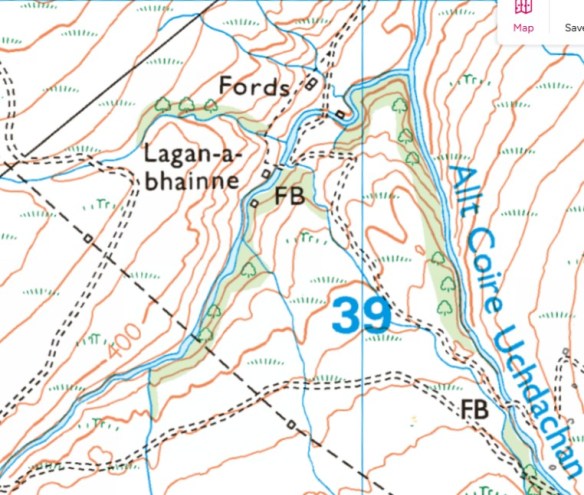

It was my intent to camp at a place called Lagan-a-bhainne, a wooded area of small valleys about 12km out from Fort Augustus. Still in the wilds, but off the high moors. When planning the trip I had spotted the area and thought it looked like a likely spot for a wild camp. My eye as someone with some experience in map-reading, was drawn to it. As on the map, so the reality on the ground: it was indeed a quite magical area where a narrow wooded valley cuts through the high moors. I found a spot to camp, taking quite some care that my tent could not be seen from the dirt road: it seemed to me that the three men I’d seen earlier would be employees of the landowner, and they might be driving through later on. Unlike in England, it is still perfectly legal to camp wild in Scotland, but why draw attention to yourself?

This was my second night by a babbling brook. I find the sound thereof, very restful. For supper I had my usual Indian: a spicy red lentil dhal, chick pea flour pancakes, and fresh spinach, all washed down with about 200ml of rather nice Shiraz. I always say, wild camping does not mean roughing it. Wild camping – any camping for that matter – is not, for me, a means to an end (as in merely low cost accommodation close to the mountain), but an end in itself. It is time spent alone outdoors, time spent in the wild countryside, time to collect your thoughts and prayers, time to be still. I came away carrying probably 22kg, of which 3kg was food and drink. I was not troubled thereby.

Interestingly, though I had picked a reasonably flat place to pitch, I could not settle comfortably at all – there was incipient backache, tossing and turning whichever way I lay. I moved through 180 degrees and slept like a baby. I woke up around 0600, which is too early at this time of year and latitude – there being another ninety minutes of darkness. But I was awake. I got up and prepared for my day. I had a breakfast of champions – cubes of bread, cubes of cheese, and chorizo sausage, all fried in a little olive oil and butter. Porridge of course. Black coffee. I did not have a dry strike, but it was a lovely morning and there was no rain – it was all condensation. I am using three separate dry bags for the different components of my tent – outer, inner and “footprint” (ground sheet), and this technique is a useful convenience, making the tent easier to pack in my rucksack, and ensuring that the wettest bit (generally the outer) doesn’t get the drier bits wet during the day.

Around 0800 then, onwards through the grey morning, trending ever downhill on a good road across the moor. After an hour or so, Loch Ness and Fort Augustus came into sight, and my heart fell – was it so close? I didn’t want to arrive there mid-morning. Actually the route has not so much a sting in the tail, as the walk-out is longer than it looks on the ground. On the map it was 12km; it just didn’t look that far. On my way down I passed an estate 4WD rumbling uphill, and a cyclist labouring along. It is a long and seemingly everlasting hill from the Fort Augustus side – rather like climbing Helvellyn from the Thirlmere side.

The road came down to another area of confused drumlins and narrow valleys full of trees, all very picturesque and rather reminiscent of the western Peak District. The road splits round a height of 228m at around 371055. General Wade went left; on a whim, I went to the right, along a 4WD road clearly very overgrown and ill-used. Well, not quite on a whim – a study of the map seemed to indicate that there was a way through some rather promising wild woods. I made the right decision! On the mountain, as 1930’s Scots climber W.H Murray noted, it sometimes pays to turn aside commonsense routine.

My path led down a long-abandoned un-made road by the side of the stream, down into the most magical valley, a beautiful and silent dell, peopled only by the sound of the rushing waters of the stream. This was the highlight of the trip! I had to carefully ford the stream. I continued, in a little trepidation that should have to turn back at the last. And indeed, the track to Culachy House was gated and very clearly marked “PRIVATE”. But there was another way – a hairpin to the right, down into another deep valley where I found, by chance as it were, the most beautiful waterfall: Culachy Falls.

From the falls a pleasant walk along a path through the woods, across the road and into a graveyard by the river. A little further on, the main road, and my walk was done.

- Day 1: From Newtonmore to Glen Markie, 25km in 8 hrs 33 mins

- Day 2: From Glen Markie to Lagan-a-bhainne, 27km in 8 hrs 7 mins

- Day 3: From Lagan-a-bhainne to Fort Augustus, 12.3km in 3 hrs 28 mins.

I stayed at Morag’s Lodge in Fort Augustus, a former hotel now trading as a hostel. For a modest fee you can share an ensuite room with bunks. For slightly more money but still well below B&B prices, you can buy an entire room to yourself. Morag’s Lodge serve supper and packed lunches and a continental breakfast, and they have a drinks license. There’s a members’ kitchen as well as a proper bar, so it has the best of both worlds. The staff were super friendly and helpful.

The first time I came to Fort Augustus was in May 2012. I’d camped wild the night before further north in the Monadliath. My diary of the time records the following:

Yesterday I drove west from Aberdeen, in wonderful hot mid-20’s weather, enjoying the quiet roads and rolling wooded hills of Deeside. I pressed on over Lecht to Tomintoul through the summer afternoon to Nethy Bridge. Then over Slochd and left down minor roads towards Fort Augustus, at this point looking for somewhere to camp. I turned left again, up a minor side road, going right up over the top into the heart of a dark and wild corner of the Monadliath. The sun was behind me as I drove, and it was glorious. I found a place to camp amidst sufficient dry fallen timber for a jamboree of Scouts to make open fires. I camped in a little copse of pine above the road. It was 9.20pm and full daylight. Sunset at this latitude in late May is 9.45pm. There was sufficient wood from where I sat to make a lovely little fire, on which I prepared sirloin steak (medium) and courgettes and (alas) instant mashed potatoes. A nice S.E Australian Shiraz made it the pleasanter still. I had brought with me 2 litres of water, for there was no running water here – I could not have camped had I not brought water in myself. A couple of times, an estate factor’s landrover drove past and stopped. My fire was making a fair bit of smoke; there was no wind and the smell was unmistakable. They could not see me, and perhaps they cared less, for they did not come looking for me. I went to bed at 11p.m and woke at 5a.m, thence dreaming my way through to 7a.m. Morning was misty, yet dry. No single drop of dew fell, which was remarkable. My breakfast was bacon, mushrooms, tomato, roll and butter, served with fresh black coffee. A breakfast of champions, particularly when served outside.

What struck me most about this camp was the silence. The only noises were the calls of birds, particularly the call of cuckoos, and the sound of sheep. I set off at 8.30a.m in deep mist, back to the Great Glen, and on down to Fort Augustus, where the sun burnt the mist off, leaving a cloudless sky, a glorious summer day. I took coffee and cake at “The Scots Kitchen” in Fort Augustus, and read the paper. Could I ask for more?

An important part of this journey today was the adventure of doing it solely using public transport. I took bus Scottish CityLink bus 919 down Loch Lochy through Spean Bridge and onto Fort William. Once in Fort William I then had to wait a couple of hours for the sleeper train to London, which left on time and arrived more or less on time at Euston at 0800 the next morning. Thence along the Euston Road again and back into St Pancras station, where it was so early, there were no decent coffee shops open yet, and I had to get a coffee from Costa. Onwards home to Derby, and my trip was complete.